Tesla, the electric car maker, is feeling its owner’s involvement in big-time politics. As stock markets fell sharply in the US following concerns over the negative economic impact of Trump’s tariffs, Tesla shares fell by 15.4%. This came after reports that while European motor sales were up in January, this wasn’t the case for Musk’s brand. In the UK, Tesla was down 45 per cent and in the EU, more than 50 per cent.

But it’s not just tariffs, or concerns about them, that is having an effect here. Elon Musk’s flirting with the far right in the UK and Europe, his Nazi or non-Nazi salute, the scrapping of US overseas aid and appearing on TV brandishing a chainsaw to slash public spending have made him an intensely divisive figure.

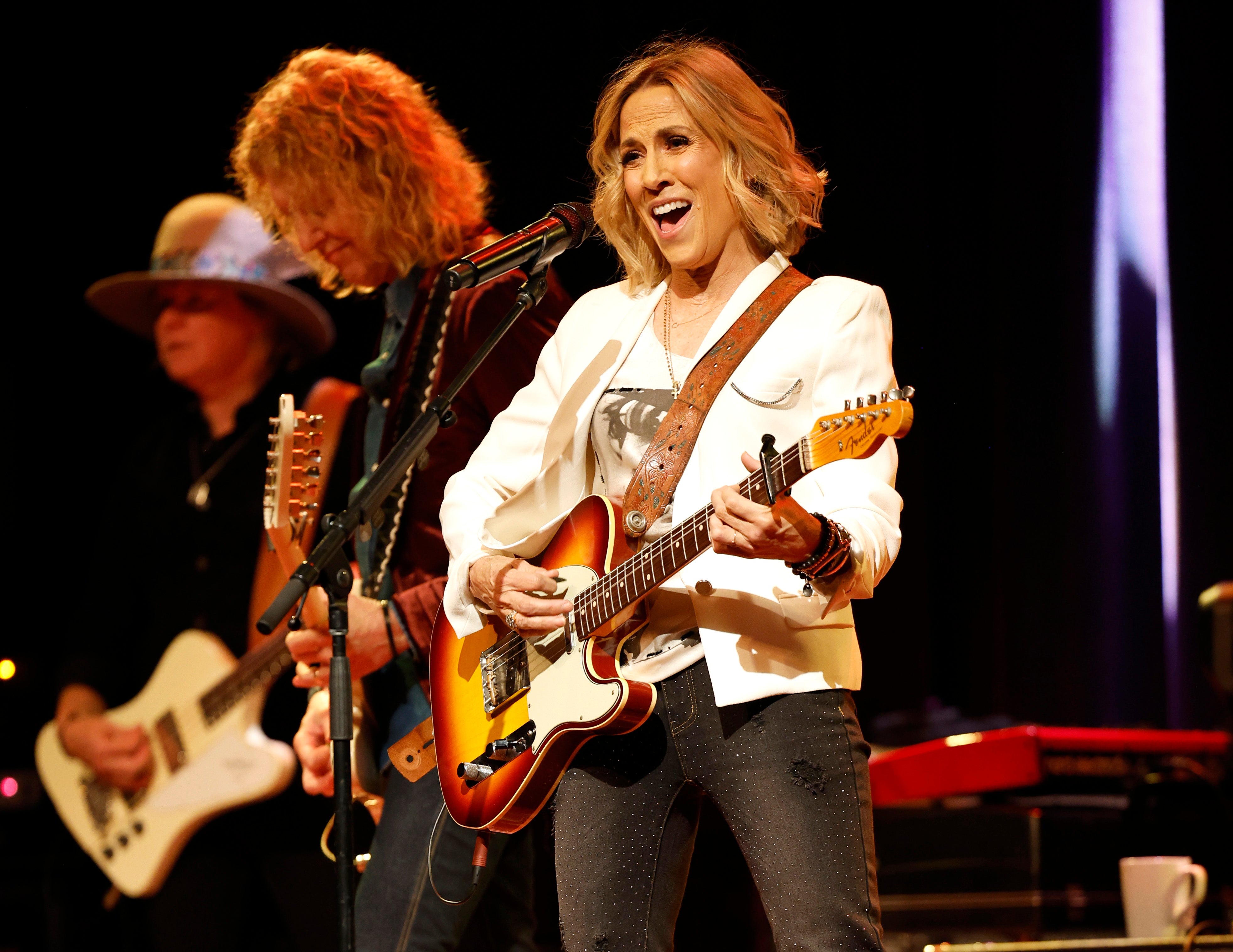

People are now actively boycotting Tesla as a brand, with Sheryl Crow being the latest high-profile figure to get rid of her Tesla in protest at Musk. The Nashville-based musician referred to the controversial CEO and Trump adviser as “President Musk” and said she was donating money to National Public Radio (NPR), which she described as being “under threat”.

While stiff competition from the Chinese and other manufacturers is a big reason for the slump in sales, one City analyst called a ”principled stand” by customers was undoubtedly becoming a factor too. Musk might not indicate so, but he and Tesla ought to be worried.

And this kind of protest stance by consumers is spreading.

Last months saw February 28 named “Economic Blackout” day. American consumers were asked to boycott all major retailers, to not make any purchases online and in-store for 24 hours. The principal aim of its organiser, The People’s Union USA, headed by John Schwarz, was originally aimed at forcing the corporate giants to rethink their pricing, as ordinary people endure rising costs of household staples, energy, housing and utilities.

The 57-year-old dad from suburban Queens, New York, formed a group with no political affiliation directed at securing “fairness, justice and real systemic change”.

But as word of the protest spread via social media, went global and turned into an anti-Trump blast. Attention for the one-day consumer action focused on companies such as Ford, McDonald’s, Meta, Target and Walmart that have ended their DEI programmes, falling in with Trump’s banning executive order. Schwarz wishes to go wider.

“For our entire lives, they have told us we have no choice … that we have to accept these insane prices…while we struggle to just to get by,” Schwarz said in a video posted on his Instagram. “February 28, the 24-hour economic blackout: no Amazon, no Walmart, no fast food, no gas, not a single unnecessary dollar spent … for one day, we are going to finally turn the tables.”

He received celebrity endorsement from the likes of Stephen King and Bette Midler, who used their social media accounts to promote the push.

The initial data shows mixed reports about its impact and one day boycotts are unlikely to have any real effect. Consumer spending accounts for 70 per cent of America’s GDP and one day’s suspension, in reality, will probably see only a tiny fraction of shoppers only putting off their buying by a day, will not make any big difference.

Schwarz, though, is planning repeats, targeting specific firms and the movement could grow. It has also hardened thinking, making those on the left think about how to target Trump and his acolytes. There is a feeling of needing to do something in the face of an emboldened president who is seemingly just doing what he wants.

Chatter has spread across the pond about how to use consumer power to make a stand. From influencers on social media to dinner parties, people are now actively sharing ideas about everything from deleting Amazon to rethinking purchasing choices to products and services which align with their values. Just recently, on their hugely popular podcast, Lily Allen and Miquita Oliver discussed whether they could live without the convenience of the Amazon cart or Google as part of the growing protest.

open image in gallery

The boycotts that work best are those that have a narrowly drawn objective and specific target in mind. Probably, Schwarz’s first consumer boycott event was too broadly defined – certainly, it has a student politics aspect to it. But if it develops into something sharper, as Musk’s opponents are doing with Tesla, then a single day of action has the potential to develop into a movement.

To stop boycotts from falling into what Maurice Schweitzer, a professor of management who researches behavioural decision making at the Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania, terms the “dustbin of outrage”, sufficient numbers must care enough to act – merely being supportive will not do it.

Leading Harvard political scientist Erica Chenoweth calculates that civil disobedience requires the backing of 3.5 per cent of the population to secure meaningful political change. Her research has inspired numerous disruptive campaigns, notably Extinction Rebellion.

open image in gallery

On its own, a boycott is likely to fail. It should be one of several tools in the protestor’s arsenal, along with raising awareness, contacting elected officials and raising funds. With social media, gaining publicity and spreading the word has become easier and quicker.

Boycotts are not new. An ethical embargo that worked was in 1791, when the UK’s parliament refused to abolish slavery. Thousands of pamphlets were distributed, encouraging consumers not to buy sugar produced by slaves. Sales plummeted, while those of Indian sugar, not tainted by slavery (produced by “free men”), soared in popularity, seeing a tenfold rise in two years.

The anti-apartheid movement against white rule and violence and discrimination against black citizens in South Africa began in 1959, with South African exiles and their supporters asking people to shun products from that country in an effort that lasted 35 years.

What began as a boycott of fruit and vegetables became tighter and more sophisticated, striking at specific companies like Marks & Spencer and Barclays with close links to South Africa. It went from being a grassroots operation to gaining acceptance on the international, high-level diplomatic stage. Finally, it helped to add to the pressure on the white minority and their leaders.

That effort was also exceptional in that it stood the test of longevity. For a boycott to stick, people must remain outraged and achieving that intensity is difficult. The urgency fades, even if in the beginning that seemed unfathomable.

“It feels intense and overwhelming in the moment, but it tapers. And that’s true for every emotion. It works against boycotts’ effectiveness,” says Schweitzer. If it causes too much inconvenience to those protesting, they will climb down.

So, to work, Schwarz needs to treat economic blackouts as the start and nowhere near the end, if he narrows down his targets and tightens the demands and highlights the issues, if he accompanies it with other weapons – then he could succeed. That’s plenty of “ifs”, but who knows? It’s far too soon to tell. It depends on an ability to galvanise and to organise, and for people to accept that they can live with a certain amount of inconvenience by giving up products and services that became so popular because of the very fact that they are so convenient and do make life so easy.

Whether this gets beyond north London dinner-party chat remains to be seen, but wounding Musk through Tesla, on the other hand, may be a more surefire bet. His wealth has fallen by more than $100bn (£79bn) since December, thanks to a sell-off in Tesla shares. That’s around 25 per cent of his worth. He’s still the world’s richest man, but there are others coming for his crown.